|

| Harry Truman winks at the camera from the back of a train. |

Without knowing it, Taft had just coined a term which would become a mainstay of presidential campaigning in the 20th century and right on through to today. It was also taken as an insult to many small towns around America, including many here in Illinois.

Starting in the mid-19th century, rail would have many important impacts on campaigning, including its role in making the nation’s rail hub, Chicago, the host of the most political conventions (25) of any city.

The first great national railroad speaking tour undertaken by a President (or in this case a President-elect) came with Abraham Lincoln’s journey from Springfield to Washington before his 1861 inaugural. Leaving from Springfield, Lincoln made remarks in dozens of cities and towns along a winding route to the nation’s capital. Lincoln spoke from podiums in ballrooms and from the back of the train in rail yards all along his route.

But in the late 19th century, active campaigning by Presidential nominees was frowned upon. As a candidate Lincoln hardly left Springfield and rarely spoke publicly. It was only after his election that he was once again able to make extended public comments.

This tradition held for another generation, with one notable exception. Arriving by train in Chicago for the 1880 convention, Congressman James A. Garfield was mobbed by reporters looking for a comment about the hotly-contested convention. Garfield, in town to support his fellow Ohioan, Treasury Secretary John Sherman, was happy to talk with them; that is, until the convention deadlocked and turned to him as its nominee.

|

| William Jennings Bryan campaigning from a train in Iowa. |

By 1912 the nation and its campaigns were changing. The furious energy of former President Theodore Roosevelt and the loquaciousness of former professor-turned-Governor Woodrow Wilson practically ensured much speechifying by the candidates, and they did not disappoint. The incumbent President, William Howard Taft, still mostly avoided the campaign trail. Roosevelt, seeking to return to the office had given up four years earlier, barnstormed the country making speeches and breaking another tradition when he arrived in Chicago to attend the convention in person, something unheard of in those days. His campaign was cut short when he was seriously wounded by a would-be assassin’s bullet in Milwaukee in October.

Wilson, meanwhile, took to the campaign trail as well. Pulling into Urbana, Illinois, Wilson was, according to reporters, aggravated with the logistics of a rail campaign. “No more private cars for me unless better arrangements can be made,” Wilson complained according to the Associated Press. The rail car “could not be attached to fast trains, and as a result Governor Wilson was forced to spend all day on the train, when he might have been in Chicago.” In Ohio the day before, Wilson’s car had been “shoved around (a rail yard) in short, quick jerks, which played havoc with the breakfast table where the nominee was seated.”

“The Governor was well received throughout the day,” the AP writer in Urbana continued. “He shook hands with people who flocked to the rear platform and waved greetings to those not so near.” Wilson edged out Roosevelt by less than 20,000 votes in Illinois on his way to becoming the nation’s 28th President.

|

| Woodrow Wilson campaigns from a train. |

New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt astonished everyone by swooping into Chicago in his airplane to accept the nomination in 1932. When he landed it seemed the era of presidential train travel had begun to fade into the background, replaced at least in part by a new technology, though FDR would continue to ride the rails throughout his presidency.

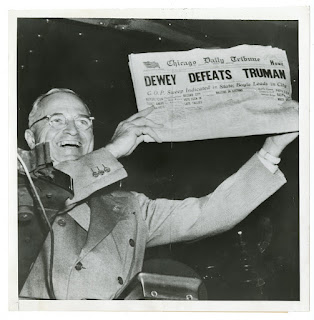

Everything changed in 1948. After Roosevelt’s death in 1945, Harry Truman assumed the office of President, but by the time the 1948 campaign got underway he was trailing New York Governor Thomas Dewey by such a margin in the polls that he had been all but written off by the experts. But Truman wasn’t going to go quietly, and in September 1948 he set out on the most famous presidential train tour in history, which inspired Senator Taft to make his ill-considered remark about “whistlestops.”

Truman would cross Illinois six times on his trip, the railroad giving him access to cities and towns which had never been visited by a President before.

“Mr. Truman was the first Chief Executive to campaign in southern Illinois and the people turned out by the thousands, breaking through police lines, swarming around and through the procession of cars and yelling a noisy greeting,” wrote The New York Times of Truman’s visit to Mt. Vernon, one of nine Illinois stops in a single day. In Carbondale Truman, “talked as he had not until now of the postwar era, of the ‘history’ he felt himself responsible for and proud of,” according to historian David McCullough.

|

| President Truman speaks from the rear platform of a train at a Whistlestop in Danville, Illinois. Photo from the Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. |

Truman was greeted in Springfield with “old-time campaign flares” similar to those carried by Lincoln’s supporters, and he sought to contrast himself with Washington power brokers and Wall Street fat cats by tying himself to Lincoln as another son of the prairie. “Lincoln came from the plain people and he always believed in them,” Truman said.

Dewey also hit the rails that fall, but in a much different, more laid-back style befitting a frontrunner trying to run out the clock aboard his train, the “Dewey Victory Special.” Avoiding controversy or any news-making statements, Dewey sought to cruise to election day. This strategy would blow up in his face during a stop in Beaucoup, Illinois, on October 12.

Dewey was preparing to speak from a platform on the back of his train car when the train suddenly lurched backwards a few feet toward the crowd, causing a moment of concern but no injuries. Dewey, standing at the microphone was furious.

“That’s the first lunatic I’ve ever had for an engineer,” he thundered. “He probably ought to be shot at sunrise but I guess we can let him off because no one was hurt.”

In a campaign known for such bland statements as “government must help industry and industry must cooperate with government,” and “America’s future is still ahead of us,” journalists seized on the rare spontaneous outburst and reported it far and wide.

The insult to a working-class railroad engineer; delivered by the man seen as the candidate of those fat cats whom Truman was challenging; aroused the anger of middle-class Americans everywhere, compounding the insult to small towns from Taft’s “whistlestop” remark. Gradually the tide began to turn and Truman went on to carry Illinois and 27 other states en route to a second term. The victory defied all expectations and the next morning, on his way back to Washington from his home in Missouri, Truman was photographed on his train holding up an Illinois newspaper carrying the most infamous headline in American political history.

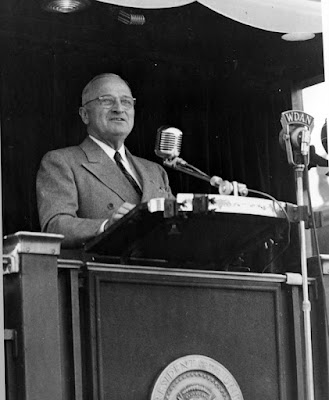

Having cemented the “whistlestop tour” into American political legend, Truman’s victory ensured its continuation. In 1960 Vice President Richard Nixon brought his train tour to downstate Illinois, telling a Danville audience about his parents rising before sunrise “in our little country grocery store to bake pies so that I and my five brothers could get the education my father didn’t have.” Later that day in Centralia he told another story about his parents agonizing over whether to buy Nixon and his siblings a pony they wanted or to pay that month’s bills. Nixon narrowly lost Illinois and the presidency that fall.

In 1976, President Gerald Ford arrived in Illinois on the 28th anniversary of his marriage to the Chicago-born First Lady, Betty Ford, and began a whistlestop tour of his own. Ford started out in Joliet, then worked south to Alton on a train called the “Honest Abe Special.” Ford referred to Lincoln’s 1858 “house divided” speech as a way of illustrating the divides he had sought to heal in the years following Vietnam and Watergate. Ford won in Illinois, but lost nationally, one of the rare occasions in the 20th century in which Illinois was not on the winning side.

Entering the 21st century, the old style whistlestop tour remains a part of presidential campaigning. In 2000, Texas Governor George W. Bush traveled to some Land of Lincoln whistlestops just after he was formally nominated at the convention. The trip did not bring Bush a victory in Illinois, but it did provide a bit of literary inspiration.

One of the Bush campaign’s top staffers, Karen Hughes, was reflecting on the hectic nature of the convention and the beginning of the fall campaign “when the conductor came over the loudspeaker and proudly announced, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, we are ten minutes from Normal.”

“If I ever write a book, that’s the title,” Hughes remarked to those riding in the train car with her. “Ten minutes from normal is exactly how I feel about this whole bizarre experience.”

Hughes’ autobiography, Ten Minutes From Normal, was published in 2004.

|

| A depiction of Abraham Lincoln's Farewell Address from a train in Springfield. Photo from the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum. |